|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Alric Lindsay

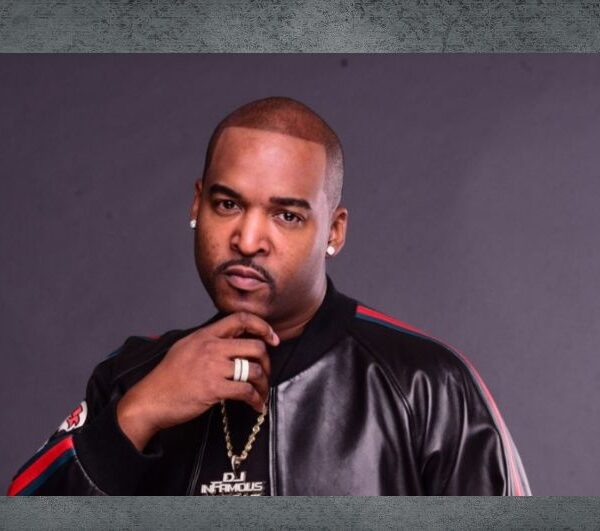

Jonathon Hughes, the lawyer for Marc Edward Chin, who faces allegations of accepting bribes under the Anti-Corruption Act while he was an officer at the Department of Vehicle and Drivers’ Licensing, stated in the Grand Court yesterday, December 17, 2024, his intention to make an abuse of process application and stay or stop proceedings against Chin. This application is expected to be heard before the Grand Court on January 31, 2025.

The basis for a stay of proceedings

Regarding the basis for staying proceedings, the July 18, 2024, Privy Council judgment of Director of Public Prosecutions (Appellant) v Chris Durham also called Bouye (deceased) and 2 others (Respondents) (Trinidad and Tobago) described “ two categories of abuse of process in criminal proceedings, as identified in R v Maxwell [2010] UKSC 48; [2011] 1 WLR 1837 (cited with approval in Warren v Attorney General for Jersey [2011] UKPC 10; [2012] 1 AC 22 (“Warren”), para 21).”

According to the reference in that judgment, Lord Dyson noted at para 13:

It is well established that the court has the power to stay proceedings in two categories of case, namely (i) where it will be impossible to give the accused a fair trial, and (ii) where it offends the court’s sense of justice and propriety to be asked to try the accused in the particular circumstances of the case.

In the first category of case, if the court concludes that an accused cannot receive a fair trial, it will stay the proceedings without more. No question of the balancing of competing interests arises.

In the second category of case, the court is concerned to protect the integrity of the criminal justice system. Here a stay will be granted where the court concludes that in all the circumstances a trial will ‘offend the court’s sense of justice and propriety’ (per Lord Lowry in R v Horseferry Road Magistrates’ Court, Ex p Bennett [1994] 1 AC 42, 74G) or will ‘undermine public confidence in the criminal justice system and bring it into disrepute’ (per Lord Steyn in R v Latif [1996] 1 WLR 104, 112F).

The judgment added:

Category 2 abuse involves a two-stage approach. First, it must be determined whether, and in what respects, the prosecutorial authorities have been guilty of misconduct. Secondly, it must be determined whether such misconduct justifies staying the proceedings as an abuse (see R v Norman (Robert) [2016] EWCA Crim 1564; [2017] 4 WLR 16, para 23).

The judgment continued:

The two categories are distinct and should be considered separately (see Warren at para 35). As it was put in R v BKR [2023] EWCA Crim 903; [2024] 1 WLR 1327, para 34: “The second limb…does not arise unless the defendant, charged with a criminal offence, will receive a fair trial. It seems clear that something out of the ordinary must have occurred before a criminal court may refuse to try a defendant charged with a criminal offence when that trial will be fair.”

The abuse of process application in the Chin case requires his lawyer Hughes to establish that that case falls within a category 1 or 2 scenario for staying proceedings, i.e., it must be shown that, because of the delay, it will be impossible to give Chin a fair trial or the conduct of the case must offend the court’s sense of justice and propriety to be asked to try Chin in the particular circumstances of the case.

As outlined in a previous story, one important point to highlight when addressing the right to a fair trial is acknowledging that this is set out in black and white in the Cayman constitution. This states: “ 7. (1) Everyone has the right to a fair and public hearing in the determination of his or her legal rights and obligations by an independent and impartial court within a reasonable time.”

In Chin’s case, his lawyer highlighted that it had been delayed for nearly six years. Concerning this, it is unclear whether any Cayman court has considered whether six years is a reasonable or unreasonable time. If it is not a reasonable time, then it may be the case that the delay could be perceived as breaching the constitutional right to a fair trial.

Notwithstanding a layperson’s logic that a potential breach of a constitutional right ought to be sufficient to raise concerns about continuation of proceedings, in practice, it appears that the threshold set by the courts to stop proceedings is high. That is, the courts also seem to require a defendant to show that there is serious prejudice against him or her so that it is impossible to have a fair trial.

Another issue is the impact of the delay on Chin’s memory of alleged events. For example, it was explained in the Grand Court that the case almost entirely rests on telephone evidence seized by police and Anti-Corruption Commission investigators five and a half years ago.

Regarding this, Chin’s lawyer said in the Grand Court that the delay “has the capacity to cause a difficulty in terms of recollection of many different conversations, many different individuals over many months.” This includes recollecting the context of some 7,000 pages of WhatsApp messages and the background discussions.

Toyin Salako of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions responded to Chin’s lawyer, Hughes, saying that what is being suggested is not a pre-trial issue. Instead, the application for a stay “is to be dealt with within the trial process,” according to Salako.

Salako added:

Mr Chin needs to be arraigned. We have a trial date, and whatever submissions Mr Hughes wants to make at the close of the Crown’s case, he can make those submissions, but it is not at this stage of the process.

After hearing from Hughes and Salako, Justice Richards stated that the hearing for the application to stay proceedings would occur on January 31, 2025.